The effects of human interference with nature and monkey arteriviruses

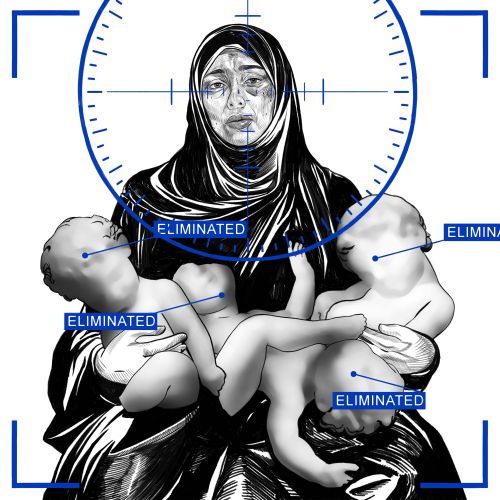

Human interference with nature often has tragic consequences. In India, the population of the three most common vulture species declined by 97% between 1992 and 2007. Birds feeding on cow carcasses were exposed to diclofenac, a cattle drug. As vulture populations have declined, the number of rats and wild dogs has increased, followed by bites by these dogs, as have cases of rabies. As a result, tens of thousands of people died each year. In contrast, after the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, the spread of which was probably fuelled by global trade, wiped out amphibian populations in Panama and Costa Rica, the incidence of malaria in Central America increased. This is because there has been a shortage of frogs, salamanders and other amphibians that feed on mosquito eggs.

Scientists from Alliance to Save our Antibiotics and World Animal Protection call for a ban on the overuse of antibiotics in livestock. Routine use of antibiotics in these creatures can lead to immunization of the bacteria. Such “superbacteria” can, in turn, transmit to humans.

Monkey arteriviruses are very similar to the monkey immunodeficiency viruses that gave rise to HIV and the AIDS pandemic. And as Sara Sawyer, a virologist at the BioFrontiers Institute at the University of Colorado in Boulder, explains, they can be just as deadly to humans. One of these, monkey haemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV), easily penetrates human cells, where it multiplies. It also appears to resist the action of interferons (a group of proteins released by body cells in response to the presence of pathogens).